By YVONNE ZIMBA

This article focuses on welfare of people with disabilities in two countries: Zambia and Finland; one developing and another a developed one. The article illustrates the individual general situation of people with disabilities in these countries and further talks  about the development cooperation between the two countries. The main purpose of this article is to bring to light the situations and assess ways in which both countries have similarities and differences in the area of disability.

about the development cooperation between the two countries. The main purpose of this article is to bring to light the situations and assess ways in which both countries have similarities and differences in the area of disability.

The article will also look at the different dynamic perceptions on disability from history to date as well as the different models that are used to view disability.

It will also give overall definitions and statistics on disability and discuss the current situation of people with disabilities in these countries.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), around 15 per cent of the world’s population, or estimated 1 billion people, live with different disabilities. They are the world’s largest minority.

- This figure is increasing through population growth, medical advances and the ageing process, says the World Health Organization.

- In countries with life expectancies over 70 years, individuals spend on average about 8 years, or 11.5 per cent of their life span, living with disabilities, reports Disabled World.

What is disability?

Disability is an umbrella term, covering impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions. Impairment is a problem in body function or structure; an activity limitation is a difficulty encountered by an individual in executing a task or action; while a participation restriction is a problem experienced by an individual in involvement in life situations.

Disability is thus not just a health problem. It is a complex phenomenon, reflecting the interaction between features of a person’s body and features of the society in which he or she lives. Overcoming the difficulties faced by people with disabilities requires interventions to remove environmental and social barriers.

People with disabilities have the same health needs as non-disabled people – for immunization, cancer screening etc. They also may experience a narrower margin of health, both because of poverty and social exclusion, and also because they may be vulnerable to secondary conditions, such as pressure sores or urinary tract infections. Evidence suggests that people with disabilities face barriers in accessing the health and rehabilitation services they need in many settings.

Statistics on disability

- According to the World Health Organization (WHO), around 15 per cent of the world’s population, or estimated 1 billion people, live with different disabilities. They are the world’s largest minority.

- This figure is increasing through population growth, medical advances and the ageing process, says the World Health Organization.

- In countries with life expectancies over 70 years, individuals spend on average about 8 years, or 11.5 per cent of their life span, living with disabilities, reports Disabled World.

- Eighty per cent of persons with disabilities live in developing countries, according to the UN Development Programme (UNDP).

Disability perceptions from history to date

Over the years, perceptions towards disability have varied significantly from one community to another. Limited literature in disability history, however, continues to pose a great challenge to students of disability studies in their endeavor to trace the development and formation of perceptions towards persons with disabilities. It is towards this end that this article seeks to present a coherent literature review on cross-cultural factors that influence perceptions towards children and adults with disabilities from a historical perspective. The final section provides a few examples that illustrate positive steps taken by the international community, and several countries, to improve disability perception.

As Roeher (1969) observes, an examination of attitudes towards people with disabilities across culture suggests that societal perceptions and treatment of persons with disabilities are neither homogeneous nor static. Greek and Roman perceptions of disability and illness are reflected in the literature.

Among the Greeks, the sick were considered inferior, and in his Republic, Plato recommended that the deformed offspring of both the superior and inferior be put away in some “mysterious unknown places” On the other hand, “Early Christian doctrine introduced the view that disease is neither a disgrace nor a punishment for sin but, on the contrary, a means of purification and a way of grace.”(Baker et al. 1953)

During the 16th century, however, Christians such as Luther and John Calvin indicated that the mentally retarded and other persons with disabilities were possessed by evil spirits. Thus, these men and other religious leaders of the time often subjected people with disabilities to mental and/or physical pain as a means of exorcising the spirits (Thomas 1957).

In the 19th century, supporters of social Darwinism opposed state aid to the poor and otherwise handicapped. They reasoned that the preservation of the “unfit” would impede the process of natural selection and tamper the selection of the “best” or “fittest” elements necessary for progeny (Hobbs 1973).

Lukoff and Cohen (1972) note that some communities banished or Ill-treated the blind while others accorded them special privileges. In a comparison of the status of persons with disabilities in a number of non-occidental societies, Hanks and Hanks (1948) found wide differences. Persons with disabilities were completely rejected by some cultures, in others they were outcasts, while in some they were treated as economic liabilities and grudgingly kept alive by their families. In other settings, persons with disabilities were tolerated and treated in incidental ways, while in other cultures they were given respected status and allowed to participate to the fullest extent of their capability.

Variations in the treatment of persons with disabilities are manifest in Africa as in other parts of the world (Amoako 1977). Among the Chagga in East Africa, the physically handicapped were perceived as pacifiers of the evil spirits. Hence, care was taken not to harm the physically handicapped. Among the citizens of Benin (formerly Dahomey in West Africa), constables were selected from those with obvious physical handicaps.

In some communities in Benin, children born with anomalies were seen as protected by supernatural forces. As such they were accepted in the community because they were believed to bring good luck (Wright 1960). Nabagwu (1977) observed that among the Ibo of Nigeria, treatment of persons with disabilities varied from pampering to total rejection.

Diversifications in perception of persons with disabilities exist in Ghana as they do in other places in Africa. Among the Ashanti of central Ghana, traditional beliefs precluded men with physical defects, such as amputations from becoming chiefs. This is evident in the practice of destooling a chief if he acquires epilepsy (Rottray 1952; Sarpong 1974). Children with obvious deviations were also rejected. For instance, an infant born with six fingers was killed upon birth (Rattray 1952). Severely retarded children were abandoned on riverbanks or near the sea so that such “animal-like children” could return to what was believed to be their own kind (Danquah 1977).

In contrast, the Ga from Accra region in Ghana, treated the feeble-minded with awe.They believed the retarded were the reincarnation of a deity. Hence, they were always treated with great kindness, gentleness and patience (Field 1937).

The degree to which persons with disabilities are accepted within a society is not directly proportionate to that society’s financial resources and/or technical knowhow. Lippman (1972) observed that in many European countries, such as Denmark and Sweden, citizens with disabilities are more accepted than in the United States. He also found that, these countries provided more effective rehabilitation services. The prevalent philosophy in Scandinavian countries is acceptance of social responsibility for all members of the society, without regard to the type or degree of disabling condition.

While throughout the world many changes have taken place in status and treatment of persons with disabilities, the remnants of tradition and past belief influence present-day practices affecting such group (Du Brow, 1965; Wright 1973).

Franzen Bjorn (1990) observed that in some communities in Kenya and Zimbabwe, “a child with a disability is a symbol of a curse befalling the whole family. Such a child is a “shame” to the whole family, hence their rejection by the family or the community. Children who are met by those beliefs and attitudes can hardly develop to their full potential: “They get less attention, less stimulation, less education, less medical care, less upbringing and sometimes less nourishment than other children.” Franzen Bjorn (1990), pg 21-26.

Thomas (1957) sees societal perceptions and treatments of persons with disabilities within cross- cultural settings as a kaleidoscope of varying hues that reflect tolerance, hatred, love, fear, awe, reverence and revulsion. The most consistent feature in the treatment of persons with disabilities in most societies is the fact that they are categorized as “deviants rather than inmates by the society.” (Lippman 1972 pg. 89).

From a cultural point of view, therefore, there are many specific circumstances that have influenced the living conditions of persons with disabilities, not to mention people’s attitudes towards them. History shows that ignorance, neglect, superstition and fear are social factors that have exacerbated isolation of persons with disabilities.

Throughout Africa, persons with disabilities are seen as hopeless and helpless (Desta 1995). The African culture and beliefs have not made matters easier. Abosi and Ozoji (1985) found in their study that Nigerians in particular and of course, Africans in general, attribute causes of disabilities to witchcraft, juju, sex-linked factors, God /supernatural forces.

The desire to avoid whatever is associated with evil has affected people’s attitudes towards people with disabilities simply because disability is associated with evil. Most of these negative attitudes are mere misconceptions that stem from lack of proper understanding of disabilities and how they affect functioning. “These misconceptions stem directly from the traditional systems of thought, which reflect magical-religious philosophies that can be safely called superstition” (Abosi, 2002).

In addition to other perceptions, social attitudes towards persons with disabilities are reflected in the family, which teaches by example customs and institutionalized values. For example, Gellman (1959) strongly believes that child-rearing practice tend to predetermine an adult’s behavior towards persons with disabilities. This concept is consistent with cross-cultural research conducted by Whiting and Charles (1953), which provides evidence that child- rearing practices influence attitudes towards illness and disability. Their findings show that beliefs about illness are influenced by significant early relationships between children and parents that deal with the child’s conformity to adult standards behavior. Their investigations examined the relationship between theories held in a culture to account for illness and the severity of child-rearing practices devised to instruct children to conform to adult standards. Intense social training was found to be related to oral, anal and genital functioning. It was hypothesized that those areas of child development which were most severely disciplined would create high levels of anxiety and would also be incorporated in theories of illness within the society. This hypothesis was supported. Also supported was the hypothesis that societies with the most severe socialization practices would create the highest degree of anxiety and guilt, and therefore would tend to blame the patient as the cause of illness.

Disability social and medical models

This model was created by Carol Gill at the Chicago Institute of Disability Research to explain how people with disabilities are seen by society and how the Disability community sees themselves. Disability studies scholars believe that an overemphasis on the medical model has detracted from full citizenship for people with disabilities. Even though people who have disabilities are very different, they are all different ages, races, and different kinds of disabilities, still share a lot of things in common – such as a common history and common experiences of being discriminated against .

Medical model

1.Disability is a deficiency or abnormality.

2.Being disabled is negative.

3.Disability resides in the individual.

4.The remedy for disability-related problems is cure or normalization of the individual.

5.The agent of remedy is the professional.

Social model

1.Disability is a difference.

2.Being disabled, in itself, is neutral.

3.Disability derives from interaction between the individual and society.

4.The remedy for disability-related problems are a change in the interaction between the individual and society.

5.The agent of remedy can be the individual, an advocate, or anyone who affects the arrangements between the individual and society.

Youth Friendly Version—Medical Model

- Disability is seen as something that could hold a person back. It is seen as something that a person should not want, or that it makes people different in a bad way.

- Disability is bad.

- Disability is a personal problem – the disability is in you, and it’s your problem.

- What will make problems better is curing the person or making them seem as least disabled as possible.

- Only professionals can help the disabled person fit in and be accepted in society.

Youth Friendly Version– Social Model (How the disability community sees themselves)

- Disability is only a difference, like gender or race.

- Being disabled is neither good nor bad, it’s just part of who you are.

- Problems come from the disabled person trying to function in an inaccessible society.

- What will make the problems and issues that people with disabilities have better is a change in society (like making things accessible for everyone).

- That change can come from the person with a disability, an advocate, or anyone who wants people with disabilities to be included equally in society.

People with disabilities in Finland

In Finland the key government Ministries are responsibility for disability law and policy implementation in their respective areas, while the municipalities are required to provide health and social services locally coordinated by the Provincial State Offices. The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health takes the lead in policies concerned with social welfare and health care, as well as monitoring services. National Institute for Health and Welfare is a new combined research and development institute operating under the auspices of the Ministry , which will also develop disability statistics and information. The Ministry of Employment and the Economy assumes responsibility in its key areas. The National Council on Disability is a national cooperative body, which involves key government departments with organizations of disabled people and their families. There are also local municipal disability councils. The Social Insurance Institution of Finland controls a range of relevant functions, including rehabilitation and vocational training. Current strategy focuses on the development of a new government Disability Policy Programme (VAMPO), based on human rights and the UN Convention.

Finnish Disability Forum encourages disabled people’s equality and participation and seeks to influence national and international policy. It has 27 member organizations. Other significant national organizations of disabled people include: Finnish Association of People with Physical Disabilities works for empowerment and equality. It has 165 organizational members with 34,000 members, controlled by a general council with 56 elected members. It is mainly financed by donation and by grants from the Finnish Slot Machine Association, as well as charges for services.

The Threshold Associations also based on human rights, as well as principles of independent living and culture. It includes 1,600 members with physical and sensory impairments.

Finnish Federation of the Visually Impaired represents the interests of blind and partially sighted people and provides services, consultancy and training (including guide dog training). There are regional associations with 80 branches.

The Finnish Association of the Deaf seeks political, social and language rights for Deaf people. It has 43 member clubs with more than 4,000 members and around 100 employees. Almost half of the income comes from the Finnish Slot Machine Association.

The Finnish Association for Persons with Intellectual Disabilities is run by persons with intellectual disabilities and their relatives, to provide support and to promote equality and quality of life. It includes more than 200 local support organizations and 18,000 members.

National law and strategy Finland has signed the United Nations Convention and the Optional Protocol. Important national laws, policies and strategies concerning disabled people include: Summary of services and benefits Services and Assistance for the Disabled Act April 3, 1987 This is the most important Act to get disability services and defines responsibilities for the provision of support. Act on special services of people with intellectual disabilities June 23, 1977 provides for special services and support for daily living for people with intellectual disability (e.g. in housing, employment, education and research).

Account of the Finnish government for the disability policy (2006) is a strategic government report on inclusive disability policy. The main objectives promote rights to equal treatment, inclusion and support (including mainstreaming policies in housing, employment and education)

Facts and figures Data on population indicate that: Population statistics in Finland include data on population by age-group population structure, population projection, area (population and GDP by region, largest municipalities, families (2007), families and children, vital statistics, foreigners in Finland and asylum-seekers and refugees.

Data on accessibility indicate that: Ministry of Transport and Communications’ Research and Development Programme for Accessibility “ELSA”A number of projects have been developed in Design for All studies within Finnish universities and polytechnics(2006) The Communication and Technology Centre Tikoteekki Tikas is a pedagogical ICT training model developed for teaching people who learn differently. A national action programme Towards Barrier-Free Communication was published by the Ministry of Transport and Communications in 2005. Since then, new research has been completed and new objectives established.

According to the latest national study, poverty and low incomes of disabled people are permanent issues in Finland although historical data is not readily available.22% of disabled people aged 25-64 have lower incomes than non-disabled people. Disabled people have an employment rate of around 25-30% and a third of them have a disability pension 2006.

Data on attitudes indicate that: The National Council on Disability (VANE) reports that, although a basic positive attitude has been found in recent attitude research, disabled people are considered as objects and not subjects. The recession of the 1990s worsened attitudes. The 2007 Special Eurobarometer on Discrimination in Europe, showed that 58% of people knew someone who was disabled) and 84% acknowledged that being disabled tended to be disadvantage in society (both slightly higher than the EU average).However, disability discrimination was not viewed as particularly widespread (only 43% thought this compared to an EU average of 53%); Only 19% thought that disability discrimination was more widespread than five years ago.78% thought that more disabled people should be in the workplace (higher than the EU average of 74%) and 86% thought specific measures on equal opportunities were needed in this field.

There is no preferential employment quota scheme in Finland Long-term support and care The municipalities in Finland maintain primary responsibility for health and social care. There is a strong public system of support based on local taxation and some means-tested fees. However, there have also been concerns about pressures on the system arising from demographic ageing, declining birth rates and economic recessions. A national report on long-term support and care has been published but not implemented. The report includes recommendations on the need for planning and co-ordination of housing and individual assistance and support; abolition of residential institutions to non-residential services; incorporation of remaining specialist institutions into the health system; acquisition of 600 flats per year; particular attention to housing for disabled children and their families.

Situation of people with disabilities in Zambia

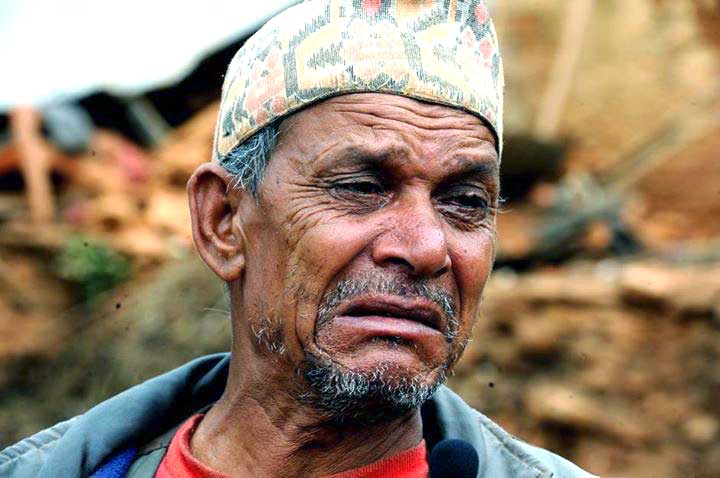

As in the rest of southern Africa, people with disabilities in Zambia are among the worst affected by negative socio-economic conditions and face stigmatization and social exclusion.

They also face physical barriers to mobility and access to public buildings; and the more complex impediments to their enjoying essential services such as education and health care, which in turn affect their chance of finding jobs.

The current situation in Zambia does not provide a context within which disability rights and the socio-economic entitlements of Persons With Disabilities (PWDs) are likely to be paid much attention. Zambia’s Fifth National Development Plan (FNDP) reports that PWDs are numerous. Throughout Zambia, and occur at all levels of society. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), PWDs constitute 10–20 percent of the population of most countries, which would mean that Zambia’s disabled population is about 1–2 million.

To a large extent, disability in Zambia is still regarded as requiring a charitable response. Traditionally, the responsibility for supporting PWDs has fallen on the family and government intervention, where it has existed, has often been channeled through welfare policies. Very little commitment has been shown at national level to addressing the causes and consequences of disability, and the generally unequal status of PWDs in Zambian society. However, it appears that the FNDP has made some headway towards realizing that, if any progress in the struggle towards achieving equal opportunities for PWDs is to be achieved, their rights and needs must be addressed in all pieces of legislation and development plans at every level of society.

On the other hand, the FNDP midterm review report published by the government contains no information on whether the objectives relating to disability and development in the Plan are being implemented, or what progress has been made on this matter by the government.

In general, the situation of Disabled People’s Organizations (DPOs) in Zambia is typical of those pertaining for all the other DPOs in the region. In Zambia there is an exceptionally large gap in capacity and resources between the umbrella body and its affiliate DPOs. The latter generally struggle for survival because they lack staff and financial support. Zambia National Federation of Disability Organizations (ZAFOD), on the other hand, appears to be extremely active and influential with competent staff and sufficient funding. It is in a league of its own in the region because it can already boast a number of successes in strategic litigation cases, and is involved at a high level in national political and development planning processes and legal reviews and reforms. It has also been working to promote the Convention on the Rights Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) in all its aspects, from lobbying for its ratification to setting up monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to monitor its implementation.

ZAFOD is also advocating the inclusion of disability rights in the new draft constitution. Interestingly, another project advocated by ZAFOD has been the incorporation of disability issues into the courses taught at law schools and schools of humanities in the country’s tertiary institutions. At the time of the interview (July 2010), ZAFOD was preparing a proposal on how disability issues can be integrated into all relevant courses, as has already been done with gender issues.

Apart from the disability organizations established by the government, other DPOs in the country include the Zambia National Federation of the Blind(ZANFOB), Zambia Deaf Vision, Zambia National Association of Persons with Physical Disabilities (ZNAPD) and the Zambia Association for Women with Disabilities(ZNADWO).

Development Cooperation between Zambia and Finland

The Finnish development assistance to Zambia dates back to the years that followed Zambia’s declaration of independence in 1964. Between 1975 and 1999, the total volume of aid disbursements from Finland to Zambia was FIM1.5 billion, making the country historically the second largest recipient of Finnish development assistance after Tanzania. The Zambian Country Programme Evaluation (CPE) aims to assess the performance of the past and current Finnish aid portfolio. The study focuses on the relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability of the bilateral development cooperation between Finland and Zambia, and on the administration of the aid. In addition, the analysis considers the coherency, or complementarily, between development cooperation and other Finnish-Zambian relations, including diplomatic and trade relations. Based on the evaluation results, recommendations are made on the preferred strategy for Finland in its future development cooperation in Zambia.

The evaluation was carried out between August and November 2001. In addition to a review of relevant documents on the Finnish-Zambian development cooperation, the Evaluation Team interviewed key stakeholders of the Finnish-supported aid activities. In Zambia, the field programme included visits to relevant institutions and organizations that have been involved in MFA-assisted operations in agriculture, forestry and education sectors as well as in non-governmental institutions selected for a detailed review. Interviews with the project beneficiaries were also included.

Disability Relevance

Disability issues have been highly relevant in the Finnish aid portfolio in Zambia. Some 80% – 90% of Ministry of Foreign Affaires (MFA) grants through Finnish NGOs have been channeled to disability-related projects in Zambia. Further, under the ESSP umbrella, project components have supported special education and the training of the teachers for people with disabilities. Results have been achieved in the area of advocacy, reflected in the increased awareness of the general public of the disability issue in Zambia. Concrete examples of achievements in the form of improved legislation, new public support institutions, increased number of specially trained teachers and increased membership in disability organizations can also be recorded. The key problem again is the very low sustainability of most Finnish supported efforts after the expiry of the MFA grants.

References

- ENABLE, UN and Disability rights http://www.un.org/disabilities/default.asp?id=18

- Disability Studies Quarterly, vol 32 no 92

- Open society for southern Africa

- Ministry of Foreign affairs in Finland

- Morris. J, Pride against prejudice, the womens press, 1991,London.