By Victoria Peel Yates

LGBT rights in Argentina could serve as idea models for other countries in Latin America, argues GSDM’s Argentina Country Corespondent Victoria Peel Yates.

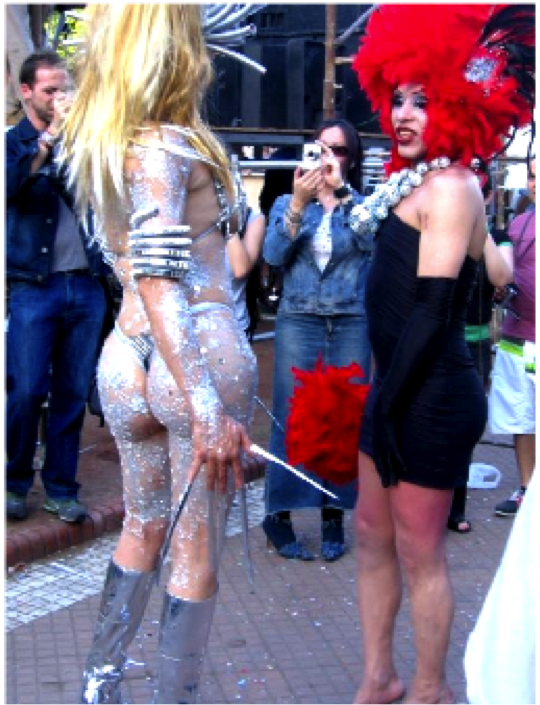

For a country synonymous with a culture of machismo, gauchos (cowboys) and a dance deeply rooted in traditional male-female dominant- submissive roles, the tango, Argentina is surprisingly leading the way for gender and sexual equality in Latin America.

Amid the recent drama unfolding in the Argentinean political arena, namely the dispute with Britain over the Falklands/Malvinas (among other things), two bills have been quietly making their way through Congress, almost unnoticed. The first was passed on 14th March 2012, and marked a huge breakthrough for women’s rights in Latin America. The bill legalised abortions for all victims of rape, a modification to an existing law that allowed abortion only if the rape victim was mentally disabled. The second bill is the ‘Ley de Identidad de Géneros’ (Gender Identity Law), which if passed will allow Argentinean citizens to change their name and gender on their national identity cards. If passed, it will reaffirm Argentina’s status as the Latin American leader in gender and sexual equality.

Argentina was the first (and to date the only) Latin American country to legalise gay marriage and adoptions, with a law that was passed in 2010, joining just a handful ofcountries that recognise gay marriage. It has some of the most progressive laws promoting gender and sexual rights in the entire region. In Chile, Bolivia, Peru, Paraguay and Venezuela there are no laws that recognise or grant rights to same sex couples. Brazil, Uruguay, Ecuador and Colombia have followed in Argentina’s footsteps by passing laws that recognise and grant rights to same sex couples. However, despite strong lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) civil rights movements, homophobia is rife across the continent, even in those countries where same sex couples are recognised.

This is manifested in violent attacks and murders of LGBT people; the most extreme example is in Ecuador, where young women are sent to horrific “clinics” to be “cured” of being lesbians. High numbers of homophobic attacks and homicides have also been reported in Chile and Brazil. Despite the growing acceptance for LGBT public officials in countries such as Colombia (where the appointment of Tatiana Pineros, a transgender woman, to head of Bogota’s social welfare agency was received with little opposition from the public), others, such as Bolivia, do not even have laws in place to prevent discrimination based on sexuality. The continent seems to be divided, with conservative religious and political views clashing with supporters of LGBT civil rights.

See Also:

- Fighting for LGBT Rights in Bangladesh: An Interview

- The International Aid Agenda and Cuban Internationalism

This is no less true in Argentina. However, the difference in Argentina is that, despite the obstacles faced, LGBT civil rights are advancing, seemingly with support from the wider public. So why, despite the dominance of relatively progressive leftist governments dominating the Latin American political arena, is Argentina unique in its efforts to improve gender and sexual equality? The strong LGBT civil rights movement and high levels of urbanisation and education only go so far in explaining the phenomenon, since these are also found in other Latin American countries.

There are several possible factors that may contribute to Argentina’s avant garde approach to gender and sexual equality. The first is that, despite being a predominantly Catholic country, attendance within the Catholic Church, at roughly 22%, is relatively low compared with its Latin American counterparts, as well as with the US. This is significant because the Catholic Church, in Argentina as elsewhere in Latin America, has been strongly opposed to the legalisation of gay marriage. Moreover, the Evangelical population, at just 2%, is tiny, compared to a growing number of followers in Mexico and Brazil and a huge following in the US. This means that despite fierce opposition to gay marriage, the Evangelical Church has very little influence.

A second key factor may be the separation of church and party; most countries in the region separate church and state, but this may not be enough. Strong opposition from Christian parties has had a profound impact on preventing the passing of laws that would recognise gay marriage. This has most notably taken place in Chile, where the Christian Democrat party has blocked several bills to recognise same sex couples. In Argentina, such parties do not exist, limiting the power of the Church within Congress.

Another reason may be Argentina’s high level of transnational legalism, referring to the ease with which Argentina imports international norms and adopts them domestically. While this is high throughout Latin America, Argentina is undoubtedly the regional leader (incidentally, the US has a very low level of transnational legalism). This means that proponents of LGBT civil rights have borrowed heavily from LGBT rights activists around the world, often replicating their arguments verbatim. This is not to say that the LGBT rights movement in Argentina lacks domestic resources. The agenda of the LGBT movement was cast as part of the country’s broader agenda on behalf of feminism, gender, reproduction, health, and sexuality, which have been part ofArgentina’s legislative agenda for decades. They used innovative strategies, such as encouraging gay couples to request marriage licences, and when these requests are refused, to challenge the refusal on constitutional grounds. Popular support for the cause was probably also won due to the actions of the Church, whose polarizing rhetoric became increasingly and openly discriminatory towards the LGBT population.

Ultimately, the final say lies with President Fernandez, who took the risk of confronting the Church and passing the controversial law. There are a myriad of reasons that she may have chosen to do so, both domestic and foreign, ranging from further splitting an already fragmented opposition to advancing Argentina’s position as the Latin American vanguard of gender and sexual rights.

It is impossible to pinpoint one reason that distinguishes Argentina from other countries in the region; many have similar histories of military dictatorships, and financial and political crises. But in Argentina, a particular set ofsocio-political factors seems to have combined to make it the regional leader in progressive social policies. The rest of the region may have some way to go, but it is likely that sooner or later they will follow suit.

[…] Argentina: the Latin American Pioneer in Gender and Sexual Equality […]

[…] Argentina: the Latin American Pioneer in Gender and Sexual Equality […]