by Deanna Morris

Cambodia Past and Present:

Although the genocide that occurred under the direction of the Khmer Rouge—followers of the Communist Party of Kampuchea in Cambodia that practiced social engineering that led to the genocide and enforced a failed agricultural reform that killed millions through widespread famine—ended over three decades ago with the dismantlement of the last strongholds in 1998, it has and continues to be enormously detrimental to Cambodia’s developmental progress.

The conflict-induced breakdown of the nation’s education system, social services and national infrastructure left the country devastated and vulnerable. It resulted in massive losses in human capital and knowledge and—as a result of landmine explosions, lack of medical treatment and/or vaccination during childhood and poor knowledge of disease prevention— in its wake it left large numbers of people disabled. Today, according to the Disability at a Glance 2010 report by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP), 4.5 per cent of Cambodia’s population—some 170,000 people—is qualified as disabled.

See Also: Tourism for Change: An Inspiring Example from Cambodia

Despite its rating as least-developed country (LDC) where 56.5 per cent of the population are estimated by the World Bank (WB) to earn less than $2 a day (adjusted for purchasing power parity), Cambodia is consistently, albeit incrementally, improving its enrolment and literacy rates and successfully reducing poverty (from 34.7 per cent in 2004 to 30.1 per cent in 2007, WB). However, marginalized, physically impaired people are still severely affected by income inequality and exclusion. This—combined with social stigmas surrounding mental and physical disabilities—negatively impacts the future livelihoods and social and educational inclusion of disabled individuals.

Socioeconomic Exclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Cambodia:

According to traditional Buddhist beliefs held by many people in Cambodia, a baby is born with disabilities to atone for his or her sins accumulated in the previous life and the child can therefore bring bad luck to the family. This cultural and spiritual stigmatization means that disabled children are not recognized in society as people deserving of education. Although government data on schooling or employment is unavailable, earlier estimates by UNESCAP indicate that 90 percent of children and youth with disabilities have no access to any form of education. Furthermore, a small-scale 2007 Action on Disability and Development (ADD) study in Cambodia’s Kandal province showed that 43 per cent of people with disabilities are illiterate, compared to only nine percent found in the non-disabled population.

According to traditional Buddhist beliefs held by many people in Cambodia, a baby is born with disabilities to atone for his or her sins accumulated in the previous life and the child can therefore bring bad luck to the family. This cultural and spiritual stigmatization means that disabled children are not recognized in society as people deserving of education. Although government data on schooling or employment is unavailable, earlier estimates by UNESCAP indicate that 90 percent of children and youth with disabilities have no access to any form of education. Furthermore, a small-scale 2007 Action on Disability and Development (ADD) study in Cambodia’s Kandal province showed that 43 per cent of people with disabilities are illiterate, compared to only nine percent found in the non-disabled population.

See Also: A Dedicated Journey: One Man’s Commitment to Children’s Rights in Cambodia

Because some employers refuse to hire disabled persons, as they fear bad omens for their businesses, these culturally imposed barriers carry on into adulthood. Therefore, lives of persons with disabilities, particularly those from already marginalized families, are incredibly difficult and economically draining due to poor educational access and lack of ability to find employment later in life.

What is Being Done?

There is an emergence of national and international non-government organizations (NGOs and INGOs) working on issues related to persons with disabilities in Cambodia, as well as increased funding opportunities through agencies like AusAID and the Australian Red Cross. One particular organization that has advanced the rights, integration and improved livelihoods of persons with disabilities is Aide et Action (AEA), an International NGO of Swiss origin, that has had a presence in Cambodia since 2003 and which operates in more than 25 countries world-wide.

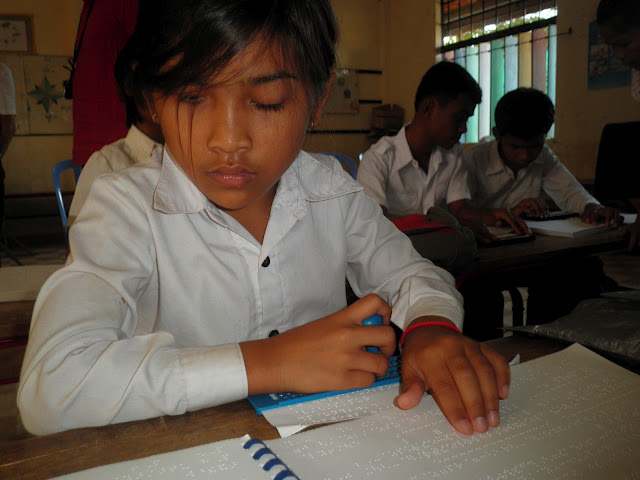

AEA’s Schooling for Deaf and Blind Children project—implemented in partnership with the Cambodian foundation Krousar Thmey—for example,aims to enhance the inclusion and rights of deaf and blind children by providing quality and effective education. The project focuses on integrating kids into the general classroom, educating teachers on how to effectively teach disabled children and providing the materials necessary for children with disabilities to advance. The project also encourages families of deaf and blind children to send them to school and advocates for the rights of disabled children in communities in order to change existing false negative cultural attitudes towards them.

To date the project has established 44 integrated classes in 13 provinces, providing education to 227 deaf students and 34 blind students. It has also given 94 public school teachers and directors specialized training to help develop skills that will allow them to better manage integrated classes and meet the needs of disabled students.

AEA recognizes that access to education is a necessary but inadequate step towards improving the lives of disabled people and that, despite the implementation of the newly established Law on the Protection and the Promotion of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, the employment sector for individuals with disabilities is still limited. In an effort towards socio-economic inclusion and poverty reduction the organization has launched a research initiative to identify the hurdles to employment that youth (legally categorized as age 15-30) with disabilities face, entitled: Identifying barriers to employment of youth with intellectual disabilities in Cambodia: determining strategies and service provisions for increasing workforce participation. The research results—due to be published in December 2012—will provide in depth information for AEA and other organizations to develop informed programs that will be key components in Cambodia’s new decade of social inclusion and enhanced socioeconomic development.

The Person Leading the Drive for Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Cambodia

Mr. Samphors Vorn knows what it is like to be excluded from accessing educational and employment opportunities in Cambodia. However, through his incredible determination, intelligence and relentless drive, he has managed to achieve success despite a physical disability, and is now becoming a leader in the effort to change discriminating practices of social exclusion in the country.

When he was born, directly after the Khmer Rouge regime, his family walked nearly 250 kilometers to a refugee camp stationed on the Thai-Cambodian border to get food and medicine. It was along the trek back to his hometown—a rural area outside of Battambang, Cambodia—that Vorn contracted Polio, which resulted in poor muscle and bone development in his right leg. “I was unable to really walk at the age of six; I wanted to go to school but could not because the school was far away,” he said. Through a personal resolve to get an education, at the age of eight, he managed to make the three-kilometer walk almost every day.

Vorn excelled in school and was determined to continue his education at secondary school that was located twice as far from his village. Despite his disability Vorn procured an old bicycle and rode six kilometers each day to attend classes even when most of his able-bodied friends dropped out because of the distance. Although his family supported him in this endeavor, some of his neighbors and other community members did not. “People would say, ‘there is no need to go to school…why would you go to school? Just stay at home,’” he remembered. Unfazed by discouragement, Vorn went on to receive the top student prize every year.

It was in secondary school, where, because of a teacher who inspired, encouraged and supported him in his educational development, Vorn developed his dream of becoming a teacher. However, due to discrimination of his physical disability, he would experience many hurdles along the way. Despite his academic achievements, for example, Vorn soon learned that people with disabilities were not allowed to enter the local teacher-training course. “This was devastating and something that really blocked my life,” he lamented.

Forlorn, Vorn returned home. With his dreams shattered, his parents became increasingly concerned for his well-being and education. With no other available options they made the significant sacrifice of selling some of their farming land in order to raise the money to send Vorn to study a Bachelor of Business Administration at the Institute of Management Sciences (IMS), where he attended business classes and also volunteered as a teacher at the Battambang Jail. At first, Vorn was fearful of public speaking and unhappy with the dreary crowded prison conditions under which he was teaching. However, he continued to volunteer his time and eventually grew the courage to lead classes on his own.

After graduation Vorn was hired to work in the Student Affairs office at his alma mater. He was still holding on to his dream of becoming a teacher, so he approached the Vice President of the University about this possibility. “He said ‘no way’, but did not cite my disability directly as an issue…rather [he] said it was because I did not have a Masters Degree.” As determined as ever, Vorn enrolled in and successfully completed in a Masters in Business Administration at Build Bright University in Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital. Unfortunately, his application a potential teaching job back at IMS was still denied and it was not until a teacher became sick and the school was unable to find a replacement that Vorn finally got his chance. “A asked the VP: ‘Why not me?’ At that point they had no choice, they had to give the position to me,” he said. Once given the chance, Vorn’s performance spoke for itself and he was rewarded with a five-year General Management Lecturer position at the university.

Having surmounted his own obstacles, Vorn was still not content with the overall treatment of people in his situation and decided that he “wanted to do something to change society and change practices in the areas related to disability.” It was then that he made the transition to the NGO sector, working as the Deputy Director for Cambodia’s Disability Action Council (DAC) and finally in his current role at AEA, where he has been for the past three years.

He draws his inspiration from his own experience. “Small support can change a child’s life,” he said. “If my friends had bicycles when we were growing up they may not have dropped out of school or if someone hadn’t encouraged me to walk I may not have ever gone to school. Education and encouragement should be a priority.”

Vorn is also currently the chairperson on the Leading Committee of the Global Campaign for Education in Cambodia and is a Technical Advisor to the Ministry of Education on inclusive education. In these positions he has established inclusive education programs promoting education and employment of persons with disabilities in Cambodia and advised the government on the adaptation of policies such as including the UN Convention (and its sub-decrees) on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. “I was focused on developing the policies, laws and master plans related to persons with disabilities and am now thinking how we can transfer these policy plans into effective implementation,” he explained.

Vorn believes that the rights of the disadvantaged, especially those of children, should be supported by Cambodia on the national level, so he is now setting his sights further afield. “I am not only focused on disability, but how to generally reach the most marginalized. It is an issue of human dignity…[and] it should be the priority of our projects,” he stressed.

Vorn has since taking his education further with a Leadership Certificate from Australian Catholic University (ACU). He has also received a medal of honor signed by the Prime Minister Hun Sen—a worthy recognition by the Government of Cambodia for his work on behalf of persons with disabilities. Today, although he is very busy with his work at AEA and DAC, he is often invited back to teach at the university he once longed so much to be a professor at.

Deanna Morris is the Senior Regional Programme Officer for Aide et Action International for SE Asia and China.

This is important