By VICTORIA GREAVES

We in the West depend upon the Amazon rainforest to renew the air while our cars puff their ozone-eating fumes. Yet our mismatched interests to “save the trees!” and power our machines threaten the people who call the Amazon their home. Is it surprising that forested areas have been carved into blocks for both conservation and extraction? The irony is not lost on the land’s indigenous caretakers whose rights are jeopardized by both.

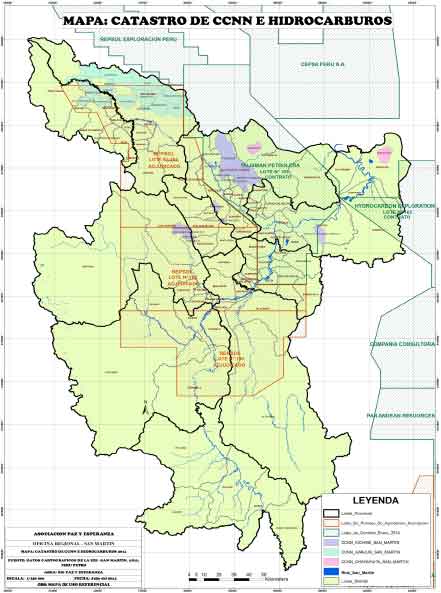

Take a look at the northern region of San Martín in Peru. A map of government concessions will show how almost the entire forested area has been cut into pieces for oil, mining, and conservation – often overlapping. Reminiscent of the Berlin Conference’s partition of Africa, powerful Western interests claim land and determine its purpose with little regard for realities on the ground.

Indigenous communities and other local farming towns battle against the government, international companies, and environmentalists for rights to their land. But few heed their cries. When restrictive or extractive policies are enacted, those who live on the land bear the scars.

Such conflicts reveal the tensions and imbalance often present in development work. We, in the international community, want to believe that development is possible and human rights can be respected, but we must ask ourselves: whose interests do we actually represent?

Hearing from local people in the developing world reveals that even positive movements, like environmentalism, can have devastating results. San Martín, Peru is one locus of these questions. Its people and their struggles show that only by prioritizing minority voices can development solutions emerge which will truly last.

What Could Be Wrong With Hugging Trees?

This question merits immediate clarification. Conservation should benefit the communities living the rainforest, so why do they hesitate to embrace it? Unfortunately, the politics in which environmental efforts are embedded is a politics of exclusion and expropriation. Local people and practices are either silenced or removed.

Environmentalism today is on the international agenda with large sums of money attached. Through the UN Redd program, the United Nations gives large grants to developing country governments to incentivize conservation. As Western powers begin to understand that the health of our world and the air we breathe are at risk, we look mainly to the developing world to resolve these problems.

Countries like Peru recognize this as a valuable opportunity. Simply by setting aside land for conservation, the government makes money. It also receives money to manage that land. So in the region of San Martín in the northern Amazon of Peru, the government has already conceded over 60% of all the land for environmental protection. It is in the process of approving more concessions which will increase the total protected area to over 75% of the entire region.

See Also: Conga Mining Project in Peru: Are Legality And Viability Enough?

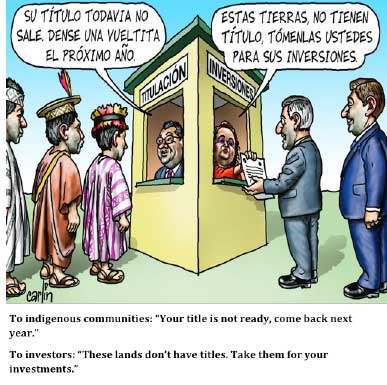

In this same region, there are over 90 indigenous communities that do not yet hold official titles to their land because the government has neglected to process them. In fact, the government does not even keep a database with documentation of many of these communities (human rights NGO’s have to do significant research, cross-checking other institutional databases to estimate the total number). Officially, the communities do not exist – the land is “empty.”

Therefore, the government can plow over entire people groups with its green spaces. For those later “discovered” living in nationally-protected zones, this puts their property at risk “if not of immediate loss… at least to a number of restrictions to its effective use,” says Peruvian human rights lawyer, Rubén Ninahuanca. Many native farming and hunting practices are prohibited within conservation areas.

Faced with these threats to their livelihood and accusations that they cannot care for their land, indigenous people protest. “We know best how to manage the forest,” shares one indigenous leader at a tense meeting to discuss a new environmental law. He and others present take the firm position to discuss environmental protection later. Land rights come first. Their traditional way of life does not oppose the need to maintain the rainforest. But the political push to maintain the rainforest may extinguish their way of life.

Conservation should benefit the earth (as our one, feeble response to climate change, it is crucial), but when paired with money-motivated governments, it becomes a weapon of displacement. Environmental interests often overlook the fundamental goal for people and the environment to live together. They chase illusions of “untouched” landscapes and forget that generations of people have lived with nature hand-in-hand.

If the government and environmentalists do not account for the interests of local people, they miss (or even reject) the need for land rights in development. Operating to please only outside interests, conservation becomes a new form of oppression.

Meanwhile…Extractive Companies Invade

If conservation repossesses the land, the extraction of oil and gold bleeds it dry. The ravaging politics of mineral exploitation surfaces commonly on the world stage. Yet even exposing this tragic tendency does not prevent the repetition of fatal mistakes.

The question “who controls the land?” will always arise in discussions of human rights and interests. As with environmentalism today, mining and petroleum companies represent big money for property owners in the Amazon. So, just as with conservation, the government sets aside zones for oil and mineral extraction. It bides its time, avoiding petitions for indigenous land titles, to wait for private high-bidders. Not only does this interfere with indigenous communities’ claims to their homeland, it may even destroy that home.

The process of gold-mining especially demands attention. There are only two environmentally-friendly, legal ways of extraction: to manually sift the sediment from the riverbeds or transport it in-bulk to processing factories. Remember the 49ers in California panning for gold? Imagine people doing that today.

The process of gold-mining especially demands attention. There are only two environmentally-friendly, legal ways of extraction: to manually sift the sediment from the riverbeds or transport it in-bulk to processing factories. Remember the 49ers in California panning for gold? Imagine people doing that today.

Not surprisingly, these methods no longer make money. So instead, property owners hire managers to supervise illegal mining operations for them. Managers bring in teams of male workers to dredge and sift the sediment with machines by the river. Further inland, away from sight, child laborers use mercury and operate finely-tuned machines to then chemically separate the gold.

This method is lucrative for property owners but otherwise devastating. The child-laborers suffer from high levels of mercury poisoning. Some mercury leaks into the river, getting absorbed by fish and ingested by nearby communities. This causes long-term health effects, interfering with the brain and nervous systems. Brothels are often created for the male workers on site. If the operation is ever discovered and shut-down, property owners avoid a legal sentence by claiming that the workers were merely trespassing.

See Also: A Mud Road to Peru

Oil extraction and its costs are more familiar to us. We have all seen pictures of the BP oil spill and gurgling tar pools. Generally, only large and well-known companies run the oil industry. They publish their export statistics and production maps, and their failures are breaking news.

This transparency, however, does not make their presence in the Amazon any less damaging. Operating with the goal of maximum profitability, large companies use low-cost methods that leave sand-and-petroleum deposits which harm the land and rivers. They could install high-cost steam technology to reduce contamination, but it is more cost-effective to pay pollution fines. Companies like Repsol have operated this way for the past fifty years.

Indigenous communities’ fears are understandable. If these invasions do not rob them of their lands initially, the contamination will force them off in the end. According to Ninahuanca, almost 9% of the total land in San Martín has been conceded to mining lots, and oil zones overlap the territories of the only 29 communities that do have titles to their land. Almost every community will be affected by some mining or oil concessions or both.

Where to From Here? An Indigenous Vision

Indigenous people’s lives intertwine with the vines and rivers of their land. Development, in their eyes, is intimately linked to land rights and protection. This is why development initiated for external interests fails, at least, for them.

They cast an alternate vision, a way for environmentalism and indigenous residence to work hand-in-hand. If the government recognizes the land rights of local communities and gives them control and aid to preserve their own forests, a new strategy emerges. Conservation becomes an instrument of development and human rights.

Peruvian anthropologist and the director of a human rights NGO, Jorge Arbocco, confirms this approach. “Indigenous communities need a secure territory that they can rely on and develop. Then, we can work with them to then recuperate land-use methods that thrive with the type of soil and forest they live on.”

Green shading: extraction zones already conceded.

He raises a critical point. If we do not provide indigenous people with security and opportunities, they begin to forfeit the more sustainable practices they once used. Pressured by the demands of the market, they too become the land’s enemies. Ravaged by oil extraction or divested of their lands, local people become desperate. They go to work with informal gold companies, start harmful, plantation-like farms, or abandon their homes and migrate to the city. Whatever the case, the land’s original caretakers are gone.

Witnessing tensions and interests play out in this one small region of Peru can help us recast the vision for our world. Environmentalism and indigenous rights are not two separate problems. They are intimately linked, and the fight is as much to heed marginalized voices as it is to check hazardous extraction and threats to the land.

What happens if we prioritize local people in the decisions that affect them and listen to the ways they care for the earth? This is the solution that indigenous leaders suggest. They may teach us that to love the earth and develop its people are, indeed, one. Arbocco neatly summarized the objective as this: “The logic of living in cooperation with the land needs to be revived. Only this will allow for development that is sustainable. We can do this, or end up like the US.”

(Victoria Greaves has a BA in cultural anthropology from Wheaton College, Illinois, USA. She interned for the human rights organization, Paz y Esperanza, in Peru in 2014 conducting research and coordinating workshops on land rights. Her interest in development has led Victoria to Guatemala, Peru, Tanzania, and Kenya, where she worked for community development and social justice organisations.)