By Hannah Bohn

By Hannah Bohn

In the wake of recent, devastating natural disasters, it is crucial to reflect on neo-colonial power dynamics and resource dependencies that disempower Americans living outside the United States. Colonialism is alive in the twenty-first century and has relegated those in Puerto Rico to second class citizenship, as demonstrated in the U.S. federal response to Hurricane Maria.

The recent metaphorical and literal flood of natural disasters has rightfully provoked serious critical reflection and demand for change. Climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of disasters, which disproportionately impact the global South. Aid is provisioned according to privilege over need and through cumbersome bureaucratic processes. Though concerns about climate change and the inequality of disaster loom large, my present concern is for the treatment of American citizens living outside the United States.

The disparity of disaster assistance between communities located within the United States and those located in U.S. territories has demonstrated an imbalance of power and privilege based on political, racial, and economic dynamics uncomfortably akin to colonialism. In light of the needs of those affected by disaster in territories such as Puerto Rico, it is essential to call attention to these neo-colonial dynamics and urge the United States to act ethically and responsibly to fulfill its obligation to American citizens.

Puerto Rico[1] is a commonwealth of the United States and its people have been U.S. citizens since 1917. This status grants them the ability to travel to the United States without a passport, serve in (or be drafted into) the U.S. military, pay federal taxes (excluding federal personal income tax), and receive some federal benefits. However, since Puerto Rico is a commonwealth and not a state, its democratic influence is minimal. Puerto Ricans cannot vote in presidential elections and their representative in the House cannot cast votes either. With such little control over their political participation, it is questionable if they are American citizens at all. In fact, a recent poll suggests over half of the American population does not believe they are.

In addition to its political disenfranchisement, Puerto Rico is subjugated economically by its relationship to the United States. The Jones Act of 1920, which restricts maritime commerce between American ports to American ships, allows U.S. based shippers to charge high rates due to a lack of external competition. Puerto Rico’s economic development has been hindered by these premiums, incurred because the island obtains a significant majority of its goods via ship from the United States. Beyond being bound to American shipping and its associated costs, Puerto Rico has accrued a massive debt of over $70 billion, the majority of which is owned by American investors.

Despite providing evidence for how Puerto Ricans are disenfranchised as U.S. citizens, the factors above do not necessarily explain why colonial dynamics continue to define U.S.-Puerto Rico relations. As an island populated by indigenous people, colonized by Spain, and won by the United States in the Spanish-American War, Puerto Rico may still be viewed as a political trophy. Given the historic and contemporary subjugation of indigenous peoples who were also defeated in their struggle against the United States, it is little surprise that predominantly Spanish speaking people of color in Puerto Rico are accorded a similar status. Further, as a spoil of war, there was no need to give Puerto Ricans political legitimacy in the form of voting rights. The lack of this legitimacy in turn minimizes the perceived worthiness of Puerto Ricans as constituents. If Puerto Ricans are unable to vote for a president, why should that president need to treat them as he does those who can vote for him?

Lacking political representation and economically dependent on the United States, Puerto Rico is essentially a twenty-first century colony.

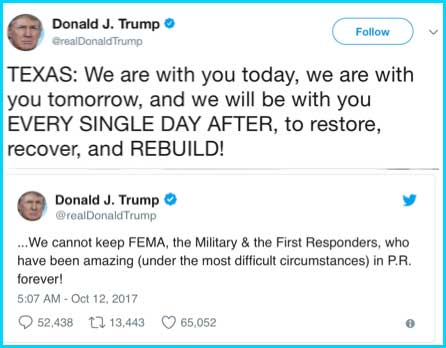

Lacking political representation and economically dependent on the United States, Puerto Rico is essentially a twenty-first century colony. If this status was previously understated, it should be evident in the wake of Hurricane Maria which made landfall September 20, 2017. The hurricane devastated the island, leaving it without power, access to communications, or clean drinking water. When FEMA finally arrived, with significantly fewer staff than were deployed to Texas (15,000 federal employees for Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands and 31,000 for Texas), they distributed seemingly insignificant amounts of food and drinking water. This disparity of citizenship status is even apparent in the tweets of our president who promises to stay with Texas “every single day” of the recovery process, while FEMA cannot be kept in Puerto Rico forever.

As a result of its economic and political status and in the wake of Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico is facing a resource dependency crisis. The United States controls the resources to which Puerto Rico wants access. With limited options in terms of providers, Puerto Rico is compelled to have an economic relationship with the United States, a relationship that was defined and codified by the United States when Puerto Rico was established as a territory. Controlling these resources and the political participation of Puerto Ricans, the United States retains power over Puerto Rico. In a post-disaster context, this power is magnified as needs become stronger and resources become more and more limited.

As donors, the United States can exercise an additional measure of neocolonial authority by defining the terms under which Puerto Rico receives assistance. Just as the World Bank mandated structural adjustment policies to accompany their loan disbursements in the 1980s, the U.S. has already demonstrated its interests in maintaining oversight over Puerto Rico’s financial situation. Last year, Congress passed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) to establish an oversight board, create a fiscal plan, and restructure Puerto Rico’s debt. Like so many paternalist colonizers, the United States granted itself the authority to meddle in Puerto Rico’s economy at no potential detriment to its own fiscal affairs (keep in mind, Puerto Rico is not included in United States GDP calculations). Now, the ability to leverage disaster assistance has brought questions of whether and how the United States will treat Puerto Rico’s debt situation and emergency assistance.

On October 12th, US Congress approved a $36.5 billion emergency aid package to address hurricane damage in Puerto Rico, Texas, and Florida, and California wildfire recovery. Of this package, $4.9 billion has been earmarked for loans to local governments in Puerto Rico to prevent an economic crisis. If the U.S. is to uphold its responsibility as a federal government, it needs to treat disaster aid to Puerto Rico as domestic aid. It needs to provide assistance, not additional loans that further indebt governments that serve U.S. citizens. Further, this assistance should be allocated without strings attached. Emergency assistance and long-term development aid are not commensurate, and PROMESA should not manipulate Puerto Rico’s need for emergency relief as leverage. As Hurricane Maria and Puerto Rico fade from national media coverage, we should not have to question the actions of the federal government and FEMA toward its citizens. We should know that it provided full and equal assistance to Americans in need, both in the United States and its territories.

On October 12th, US Congress approved a $36.5 billion emergency aid package to address hurricane damage in Puerto Rico, Texas, and Florida, and California wildfire recovery. Of this package, $4.9 billion has been earmarked for loans to local governments in Puerto Rico to prevent an economic crisis. If the U.S. is to uphold its responsibility as a federal government, it needs to treat disaster aid to Puerto Rico as domestic aid. It needs to provide assistance, not additional loans that further indebt governments that serve U.S. citizens. Further, this assistance should be allocated without strings attached. Emergency assistance and long-term development aid are not commensurate, and PROMESA should not manipulate Puerto Rico’s need for emergency relief as leverage. As Hurricane Maria and Puerto Rico fade from national media coverage, we should not have to question the actions of the federal government and FEMA toward its citizens. We should know that it provided full and equal assistance to Americans in need, both in the United States and its territories.

Time has come to show compassion for our neighbors rather than question their ability to pay back debts we put upon them.

Puerto Rico as a twenty-first century colony makes the United States a twenty-first century colonizer. The time has come to wrestle with the reality that the United States defines the terms of Puerto Rico’s political and economic capacity, and subjects its citizens to a second-class status. Hurricane Maria has provided a critical moment for the U.S. to acknowledge the neo-colonial relationship by which it has hindered the economic and human development of its own citizens. The time has come to be generous with assistance for those U.S. citizens facing the same disasters as U.S. citizens in Texas or Florida. The time has come to show compassion for our neighbors rather than question their ability to pay back debts we put upon them. We must acknowledge the historical-cultural context that frames Puerto Rico’s economy, political participation, and social life, and the role we played in its current devastation. American lives are at risk if we do not.

[1] For the sake of the scope of this argument, I limit my focus to Puerto Rico. Here I recognize U.S. citizens residing in other insular areas of the United States: the US Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands.

(Hannah Bohn is a Master of Development Practice candidate at the Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota.)